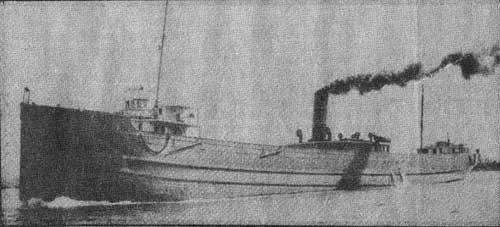

| DISASTER STRUCK THE carferry Marquette

and Bessemer No. 2, Dec. 9, 1909, just off Conneaut, the ships home port.

Captain R. R. McCleod and his 36 crew men were lost.

By CATHERINE

ELLSWORTH

Staff Writer

ASHTABULA COUNTY -

Lake Erie was the last of the Great Lakes discovered by the white man,

although it carried the first ship to travel to the upper Lakes, LaSalle's

Griffin in 1679. Later, it also carried the first steamboat, the

Walk-in-the-Water.

The Griffin, a mere 60 feet long, was a 45-ton schooner

that carried seven cannons and boasted a golden griffin on its prow.

On its maiden, the only voyage, it carried an important man, Father

Hennepin, who was called the wandering priest, and sometimes, "the

cheerful liar," writing his colorful and imaginative impressions of what

he saw.

Hennepin wrote

The priest wrote that the name, actually called

Erie-Tejocharontiong by the Iroquois Indians, had, on its southern shore,

"a track of land as large as the Kingdome of France." He called the

Lake "a vast reach of lonesome waters surrounded by wilderness, with,

along the trackless shores a dream of great cities, an infinite number of

considerable towns and an inconceivable commerce." His prophetic

statement became reality 200 years later.

Sail and steam ages

There have been two ages of transportation on

the Great Lakes: The Age of Sail and the Age of Steam. The Age

of Sail began in 1800, ranging into the beginning of the 1900s, reaching

the peak in the 1860s. At that time, there were 1,855 commercial

sailing ships on the Great Lakes.

The Age of Steam began in the mid-1800s to the present,

with the peak, as far as numbers being at the turn of the century, when

there were 17792 steam vessels on the five lakes.

Graveyard of ships

For many decades, the loss of life, annually,

was somewhat appalling, averaging more than 1,000 dead every year.

In the year of 1873 alone, there were 1,021 disasters, which included 250

collisions. With figures like these, the Great Lakes became a

graveyard of ships, with more than 15,000 shipwrecks known to the year

1980.

Beyond the loss of life, another staggering statistic

is seen. The goods and monies left in the wrecks amounts to more

than $1 billion, turning the Great Lakes into treasure troves for the

adventurous and daring.

Gold and goods

Gold and silver were used for pay and for

goods for many years, accepted readily anywhere, for trade. Crews

were paid in gold and silver, with almost all ships carrying a safe or

strong box for security, usually in the custody of the captain of a

vessel.

Experts say that $10,000 in gold that went to the

bottom in the 1800s is worth about $100,000 today. In addition,

coins of that time are worth thousands of dollars today, though their face

value was only a few dollars at the time.

Valuable cargoes

The cargoes which remain in Lake Erie's mud

have in some cases increased in value. Time has a way of turning

such things into collector's items, however out of reach they may seem to

be. These things have been kept fairly quiet, as ship owners and

insurance companies of old did not want the public to know or try to

recover such valuables.

Marquette and Bessemer

One of Lake Erie's

ghost ships is the carferry Marquette and Bessemer No. 2. The ship

was only 4 years old and considered a strong and true vessel as it headed

out of Conneaut Harbor on Dec. 9, 1909.

Filled with railroad cars that were loaded with coal

and steel, the Bessemer headed out into a heavy storm, bound for Port

Stanley, Ontario. Her crew of 36 men was under the command of Capt.

R. R. McCleod. His brother John was serving as first mate.

Ship disappeared

The ship never reached its docking at Port

Stanley, though it is thought it came near the port, only to be turned

back by the severity of the storm. The captain is thought to have

attempted to return to Conneaut.

Three days after the Bessemer disappeared, a lifeboat

was found about 15 miles off Erie, carrying a grim cargo of nine frozen

bodies. Five of the bodies were frozen in a sitting position, while

the other four were huddled over the body of a young man, as though they

had attempted to keep him warm. Of the nine, seven men were Conneaut

residents, plunging that community into shock and grief.

What happened

While no one will ever know what actually

happened, it is thought the railroad cars broke loose, possibly smashing

the low stern gate, allowing the raging waters to engulf the vessel.

This had nearly happened just one month before, Capt. McCleod had

reported.

It is said that workers on the Conneaut dock reported

hearing a distress signal form a ship about 1:30 a.m. Also, the

captain of a freighter riding out the storm at anchor outside the

breakwall claimed he saw the black shape of the carferry pass him headed

east at the time.

The losses

Whatever the cause, facts list a cargo of 30

loaded cars and 36 lives lost, with 18 bodies eventually recovered.

It is also reported that monies in the ship's safe would not be worth

between $25,000 an $50,000.

The ship has reportedly been seen from the air on clear

days, sunlight showing clearly the hull. But, so far, it has not

been located by boat. It is thought to be in about 10 fathoms of

water, about eight miles northeast of Conneaut Harbor, remaining one of

the elusive ghosts of Lake Erie.

Black Friday

The blackest day of Lake Erie shipping

history occurred Oct. 20, 1916, when a monster storm spent its full fury

on this most treacherous of the Great Lakes. Four ships were caught

in the 70 mph winds of the open lake, all going to the bottom.

The four ships were the schooner D. L. Filer, the

lumber hooker Marshall F. Butters, the Canadian steamer Merida and the

whaleback freighter James B. Colgate. All four of the captains

stayed with their ships to the last moments: Three living to tell

their stories; two being the only ones left of their crews.

The steamer Merida

Three days after the storm, the bodies of the

crew of the Merida were found floating in the middle of the lake in life

preservers, 23 men lost in all. No other sign of the ship was ever

found. It had last been sighted by another ship, about 10 miles off

Southeast Shoals, with the Merida fighting a losing battle with the

furious storm.

The Marshall F. Butters

The lumber carrier Butters carried 13 men

that fateful day, coming out of the Detroit River, bound east on Lake

Erie. Experts say her cargo of shingles and lumber shifted because

of the high seas, causing the ship to list.

Before the frantic crew could equalize the cargo, water

crashed over the ship. The members of the crew managed to lower a

life boat, while Capt. McClure and two other crew members stayed with the

sinking ship. The captain distress signal with the steam whistle

before the boiler fires went out, but there was no way it could be heard

above the storm.

To the rescue

Nearby, two freighters tried to get to the

stricken vessel. One, the F. G. Harwell, managed to pick up the men

in the nearly-swamped life boat. The other, the Frank R. Billings,

was commanded by a Capt. Cody, who, while unable to hear the whistle, read

the distress call by the puffs of white smoke from the whistle.

Cody, in a uncanny display of seamanship, maneuvered

his ship in a circle around the Butters, dropping storm oil, somewhat

calming the waters. He and his crew managed to pull the remaining

crew members of the Butters aboard just before the ship broke up.

Strangely enough, the 13 men were rescued just 13 miles from the Southeast

Shoals.

The D. L. Filer

The schooner Filer was also near the western

end of Lake Erie that Black Friday, nearly in the safety of the Detroit

River. But fate intervened, with overwhelming amounts of water

crashing against and over the ship that was loaded with coal.

All six of the crew members hurried up the foremast to

escape the rising waters, while the captain clung to the aftermast by

himself. The foremast snapped under the excess weight, drowning five

of the six men. The sixth swam to join the captain.

All night fight

The two men clung to the mast all night,

with, at one time, a ship coming so close to them that it nearly hit them.

Still, they could not make those aboard hear their cries. In the

morning the passenger ship Western States spotted the pair, hurrying to

the rescue. Unfortunately, only the captain survived, as the crewman

with him, exhausted from the ordeal, slipped beneath the water just as

hands were reaching to lift him to safety.

The James B. Colgate

The fourth loss that day on Lake Erie was the

whaleback ship the James B. Colgate, loaded with coal and a crew of 26,

commanded by veteran sailor Capt. Walter Grashaw. Having served as

first mate of the vessel for 10 years, Grashaw had received his command

only two weeks earlier.

The sturdy ship was opposite Erie, when the intensity

of the storm, actually of hurricane strength, sent water into the hold.

Soon the vessel was listing, the crew aware of what was about to happen.

At 10 p.m., the Colgate went down, bow first.

The crew lost

With the raging winds having cleared the ship

of any materials that might have forded rescue, there was nothing but life

vests to hold the men. These were of little use against the waves,

and served only to keep the 26 dead bodies afloat.

Grashaw was eventually rescued, on the following Sunday

morning, half dead, still clinging to remnants of a raft. He had

seen his ship and the men of his first command die, with only his own

supreme will to live brining him through Black Friday.

A miraculous escape

One of the most unbelievable, yet true

happenings of Lake Erie, occurred in the fall of 1833, and strangely

enough, involved a woman rather than a sailor. The schooner New

Connecticut was caught in a squall between Conneaut and Erie. A Mrs.

Lynde was in her cabin below decks when the ship rolled over on its side.

She was the aunt of one of the most well known captains of the times,

Capt. Gilman Appleby.

Water engulfed the cabins so fast, that no one figured

anyone in the cabins so fast, that no one figured anyone in the cabins

could survive, so the crew lowered a boat and left, leaving the

still-floating ship to sink. Three days later, the distressed

Appleby asked another captain to try to get the body of his aunt off the

wreckage if it cold still be found.

Wilkins' attempt

His friend, Capt.

Wilkins, found the New Connecticut wreckage, drifting on its side, full of

water. He sent a boarding party with a search pole, which was shoved

repeatedly through the side of the hull. With no human contact

apparent, it was assumed the body had floated out into the lake.

Wouldn't give up

Determined that Mrs. Lynde should have porper

burial, Capt. Appleby would not give up. Taking Mrs. Lynde's son

along, he went to the wreck, taking a work boat with equipment to right

the vessel and bring it to port.

When the ship was nearly upright, Mrs. Lynde appeared,

walked up the stairs through the water, facing the startled workers.

She had been in the vessel, in water up to her arm pits, for five days and

nights. She could only stand all that time, even sleeping brief

moments. She had a single cracker, and an onion which floated by,

for food.

The will to live

She had heard the Wilkin's search party, but

could not make them hear her. She was nearly touched by the pole

they shoved through the hull, but again, was not heard. The will to

live during seemingly impossible circumstances had once again sustained

life.

|